5 Literary Allusions You Can’t Miss in The Sympathizer

And why the character of “the communist agent” matters

[Note: This essay contains significant references to rape and sexual violence.]

(Hoa Xuande as the Captain in HBO’s The Sympathizer)

Viet Thanh Nguyen’s mordant debut novel is the life story, told in the first person, of an anonymous communist double—no, triple?—agent, the misbegotten, illegitimate son of a French priest and a teenage peasant whom the priest saved from famine during the Second World War. The press kit for HBO’s recent adaptation calls the autodiegetic narrator The Captain, which is as good a name as any other; he sporadically uses the aliases Vo Danh (Nameless) and also Joseph Nguyen, which is not incidentally the author’s own baptismal name, as well as his father’s.

Since it first hit bookstore shelves in 2015, reviewers have called attention to the segment of the story satirising Apocalypse Now, and their response to the new HBO miniseries adaptation seems to take a similar tack, especially as Nguyen himself has said that a childhood misspent on watching uncensored American war films had a huge influence on both his sense of self and the development of The Sympathizer.

Nevertheless, I find myself irked by the tendency towards a superficial focus on the Apocalypse Now arc, which I find goes hand in hand with how some reviewers have practically fetishised the quote “All wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory” as emblematic of Nguyen’s thesis in The Sympathizer. Both ways of reading obscure how his central preoccupation in The Sympathizer—and across his entire oeuvre—is, in fact, the concept of just memory:

Something or someone is always forgotten, especially in dualistic, binaristic conflicts where the suppressed, the excluded, the minoritized, or the forgotten simply want to be remembered in a mirror image of dominant memory. One peril my book skirts is the reinforcement of this duality, the idea that the war was fought between two sides, American and Vietnamese. In reality, the war had many national participants, and nations were themselves fractured.

In other words, Nguyen’s work treats violence among Southeast Asian subjects as a serious ethical and aesthetic concern—but the popular reception risks getting distracted by the American emperor going unclad, an element of the narrative that makes itself an obvious spectacle for criticism but is also very low-hanging fruit.

Start with the cinema

(For what it’s worth, I think that the Apocalypse Now satire—a term I’m using as shorthand, since Nguyen was also commenting on The Deer Hunter and Full Metal Jacket—is much less sharp than it could have been. When it comes to recent novels that play with the idea of Asian American media representation, I think Charles Yu’s Interior Chinatown [2020] was funnier, and Gina Apostol’s Insurrecto [2018] was better.)

So I was gratified by The Washington Post’s review of the HBO series, where critic Lili Loofbourow astutely notes that the injunction for the narrator to “start with the cinema” during his interrogation “might be the show’s (and the Captain’s) mantra. Both squeeze in references to ‘Death Wish’ and ‘Emmanuelle’ to set up an interrogation scene taking place in an empty movie theater—which of course permits everyone to comment on the scene’s theatricality.”

Because the dramatic climax of The Sympathizer is not the Apocalypse Now subplot, but what happens in that cinema: a horrifying, graphic rape that goes on for four pages, with the reader as much a helpless witness as the narrator.

The woman who is the object of that rape is a comrade of the narrator, yet unaware of his true identity. Known in the text only as “the communist agent,” her character first appears in the narrator’s memory of her arrest three years prior:

She was younger than me, but she was wise enough to know what awaited her, too. For just a moment I saw the truth in her eyes, and the truth was that she hated me for what she thought I was, the agent of an oppressive regime. Then, like me, she remembered the role she had to play. Please, sirs! she cried. I’m innocent! I swear!

Characterising the extended rape scene as “the denouement of The Sympathizer,” film scholar Sylvia Shin Huey Chong brilliantly argues that it is an extension and culmination of the narrator’s fascination with visual/visceral representation. Importantly, Chong asks what purpose these scenes serve: “If the rape of the communist agent has its analogue in The Hamlet’s rape of Mai [in the Apocalypse Now satire], can one savage the representation of Mai’s rape as exploitative while commending the rape of the communist agent as artistic, perhaps necessary?

“Just as Nguyen cringes in ‘intense feelings of disgust, horror, shame, and rage’ when he sees himself as gook on-screen… I likewise cringe as I feel thrust into the position of these raped women.”

Chong concludes with the observation that “[t]he violation of the female Vietnamese body sets into motion the violation of the nation and the reclamation of humanity through inhumanity. They cannot rape themselves; they must be raped.”

(Nguyen must have read Chong’s article in PMLA, “Vietnam, the Movie: Part Deux” [2018]. In The Committed, the second instalment of the planned Sympathizer trilogy, the narrator describes himself as having “a screw loose, the trusty screw that had, for years, held together my two minds … I was no longer screwed—humanity’s universal condition—but was instead unscrewed.” Though the narrator tries to embrace what is flippantly called “the CIA’s unofficial motto: FUCK THEM BEFORE THEY FUCK US,” it turns out that he has been rendered impotent—cannot fuck—because, unlike the narrative’s victims and survivors, he himself, unscrewed, unfucked, cannot access a “universal condition” revealed to be cast as female.)

Through the allegory of impotence, The Committed makes it even more unambiguous how the experience that Chong describes as the “textual restaging and ‘rememory’ of the repressed rape scene” is integral to who the narrator has become; and the undead communist agent, who helped arrange the narrator’s patricide and who viciously haunts him in The Committed, is shown to be his other self, as illustrated by some literary allusions that stud the bibliography of Nguyen’s intensely intertextual writing.

1. When Heaven and Earth Changed Places by Le Ly Hayslip (1989)

At the outset of his scholarly career, Nguyen made his bones with an analysis of (Phung Thi) Le Ly Hayslip’s groundbreaking collaborative autobiographies When Heaven and Earth Changed Places and Child of War, Woman of Peace. His dissertation work on Hayslip led Lisa Lowe to hail him as a rising star, along with other academics like Colleen Lye, in the essay “On Contemporary Asian American Projects” (1995).

Nguyen argues that “Asian American critics tend to see texts as demonstrating either resistance or accommodation to American racism,” and “evaluate resistance as positive and accommodation as negative, without questioning the reductiveness of such evaluations.” In his reading, Hayslip navigates the binary in a “flexible strategy” where “[s]he adopts the guise of and is adopted as the emblematic (female) victim.”

His interpretation is perhaps too cynical for my taste; Nguyen instinctively recoils from her stated desire, as addressed to an American reader, “to forgive you and be forgiven by you in return,” arguing that it “implies a symmetry of power between nations that did not and does not exist.”

What interests me more is Hayslip’s own progression, within the first three chapters of When Heaven and Earth Changed Places, from a peasant childhood collaborating with Communist guerillas, to a subject who rejects resistance–accommodation.

At that point—after she is accused of betraying the Communists, and raped by her would-be executioners at just fifteen years old—Hayslip declares: “Both sides in this terrible, endless, stupid war had finally found the perfect enemy: a terrified peasant girl who would endlessly and stupidly consent to be their victim—as all Vietnam’s peasants had consented to be victims… To resist, you have to believe in something.”

Beyond “appeas[ing] the concerns of the First World subject,” as Nguyen understands her writing to do, Hayslip is articulating here the same weary refusal of a reductive binary as in, say, Jade Ngọc Quang Huỳnh’s South Wind Changing (1994), when he calls politics “a messy business” and “all lies”; in fact, her statement would not be out of place in the mouth of the narrator of The Sympathizer, either.

2. Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth (1969)

Nguyen recently admitted on Instagram to what I’m sure we all already knew: “As for PORTNOY’S COMPLAINT, I read it as a boy and could never forget an infamous episode where Alex Portnoy, horny adolescent who masturbates with anything he can get his hands on, finally gets his hands on a….slab of liver. This would inspire…well, if you’ve read the book, you know what it will inspire.”

When I first read The Sympathizer, I screamed at the infamous scene in which the teenaged narrator masturbates into a raw squid. This is just to say, he might as well have told his mother, I have defiled the squid that was in the icebox, and which you were definitely saving for dinner.

(In Violet Kupersmith’s fantastic postcolonial horror thriller, Build Your House Around My Body [2021], a woman morphs into a squid to swim away from Vietnam—probably to escape characters like the narrator of The Sympathizer, and who can blame her?)

But Portnoy and the narrator of The Sympathizer have more in common than dinner desecration. Roth’s novel, after all, ends with its own extended sequence of attempted rape. Paradoxically aroused from being insulted as an emasculated Diaspora Jew—i.e. his double-conscious anxiety about a persona as “frightened, defensive, self-deprecating, unmanned, and corrupted by life in the gentile world”—Portnoy assaults an Israeli settler while fetishising her in freely revealing terms as “big farm cunt,” “ex-G.I.,” “mother-substitute,” “virtuous Jewess,” and “healthy, monumental Sabra.”

Read today, the character of the “gallant Sabra” Naomi points to both the allure of national self-determination and the contradictory bloody-handedness of its concomitant act of violent national dispossession. Yet it is especially significant that this representation of nationalist anxiety is cast in explicitly gendered and sexual terms. Given the well-worn history of emasculation as a racist and antisemitic trope, it’s not their masculinist response that is surprising, but the autodiegetic narrators’ diffident affect over their own compensatory hypersexuality.

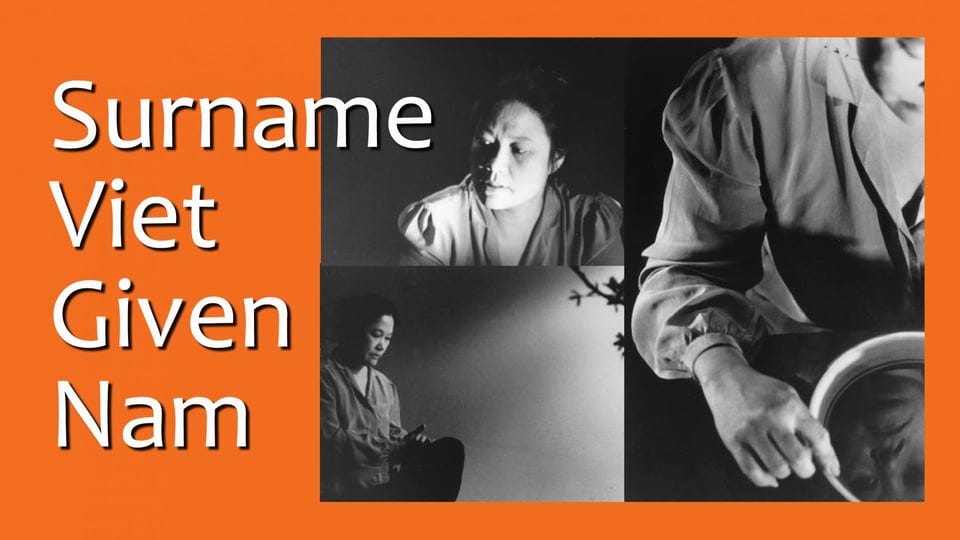

3. Surname Viet Given Name Nam by Trinh T. Minh-Ha (1989)

Another impossible-to-miss reference in The Sympathizer is even more closely tied to the character of the communist agent.

Because she is never named, she serves as foil to the similarly anonymous narrator; yet, where he uses the alias Vo Danh in The Committed—that is, he calls himself Nameless—she assumes the identity of the nation. As the gang rape begins, she declares, “My surname is Viet, and my given name is Nam!”—a proclamation that he calls “defiant,” which is the same adjective used to protest against his own phallic failure.

Nguyen has shamelessly borrowed the line from feminist filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-Ha’s Surname Viet Given Name Nam, as he notes in an interview for the Asian American Writers’ Workshop online publication The Margins:

I was thinking about the tradition of representing Vietnam through women as something that not only foreigners do but something that Vietnamese people themselves do. The moment when the communist agent says that is an allusion to the Phan Boi Chau story, which is also a part of Trinh T. Minh-Ha’s movie, Surname Viet Given Name Nam. The young woman, when she encounters someone who asks her if she is married, says “Yes, and his surname is Viet and his given name is Nam.” I wanted to both allude to this moment and undercut it, because the agent is not married to the country, but she embodies the country. The setting, a movie theatre, is also an allusion again to the movie Surname Viet Given Name Nam […]

I wanted to show that this was something that wasn’t simply happening in terms of what the West was doing to Vietnam but what Vietnamese were doing to themselves as well. In other words, the rape of Vietnamese women was also being done by Vietnamese men. The Vietnamese are at least partially responsible for what they did to themselves. I didn’t want to turn away and put the blame squarely on the Americans or the French, although that blame is there. I wanted this to be very specifically a moment of Vietnamese-on-Vietnamese confrontation and responsibility because, again, this is part of how we reclaim our subjectivity: we aren’t just victims but victimizers as well. This is a part of our history that we all find very difficult to confront. We would much rather blame other people or other sides. That’s important, but we also need to look fully at how “we fucked ourselves,” which is one of the key lines at the end of the book.

I find this conversation with Paul Tran to be one of Nguyen’s best commentaries on The Sympathizer, because it came out in 2015 and precedes his superstardom. In this instance, I think his remarks thoughtfully say it all…

4. The Lotus and the Storm by Lan Cao (2014)

The attention-grabbing conceit of The Sympathizer is that its protagonist is “a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces”—that last phrase so iconic that Nguyen would go on to use it as the title of his own memoir (or, formally speaking, anti-memoir).

By the end of The Sympathizer and the start of The Committed, the narrator’s declaration has become quite literal: He experiences a split into his two “disembodied minds,” turning into “me and myself,” and the narrator becomes we.

Meanwhile, Lan Cao’s The Lotus and the Storm, which was published not long before The Sympathizer, contains multiple first-person narrators—including the eponymous Mai and Bão, who share one body. Midway through Cao’s novel, Bão introduces herself by telling the reader, “There is a medical word in this country [the United States] to describe Mai and Cecile and me. Our madness was once called multiple personality disorder but now it is coined dissociative identity disorder,” the result of Mai’s traumatic experience of a battle during the war.

(Bão brings this diagnosis into question in the next sentence, diminishing Western psychiatry by adding, “When the thay phap told our parents years ago that a spirit might have seized Mai’s body and soul, Father associated her white-hot anger and many indecipherable moods with alien demons,” and also suggesting that he “saw me as someone his dead child, Khanh, my sister, had somehow been reborn into.”)

The Sympathizer’s ability to represent we is the consequence of the outrageously contrived travel path that the narrator takes over the course of the two books: Moving through the roles of a North Vietnamese spy, a South Vietnamese captain, an airlifted evacuee from Saigon, a refugee in California, a prisoner in a re-education camp, a boat person, and a refugee in Paris, the narrator traverses the multiple global identities of individual members of the post-war Vietnamese diaspora, and takes on a representative role. However, this we fragments early on; and, moreover, the text is ambivalent as to when we is speaking for a collective, or the voice of a single schizophrenic. Unable to access feminine trauma, the kaleidoscopic narrator of The Sympathizer both purposefully pursues representation and strains at its limits.

5. Blue Dragon, White Tiger by Trần Văn Dĩnh (1983)

Near the end of Blue Dragon, White Tiger, I thought that we were coming ashore on familiar ground, as the hero Tran Van Minh, disillusioned with the revolution that he had idealistically supported, leaves the country by boat.

(Possibly the nicest exodus ever; in a mood of “romantic excitement,” the author has its occupants read poetry aloud to mutual applause, and the boat is captained by an emeritus professor who declaims gloriously that “we, the ‘boat people of Vietnam,’ are carrying the banner of the will to live free” as a “message to humankind.”)

(Still from Ann Hui’s Boat People [1982]. Read Vinh Nguyen’s essay on the film here.)

The final chapter of the novel, however, crams a shocking barrage of developments into an eventful dozen pages.

On the journey, Minh finds himself erotically transfixed by a fellow passenger; he first writes in his diary, “Must confess, she’s very attractive and I feel a strong desire for her,” then remarks much more floridly some days later, “In the milky light of the starry night, I detected a sarcastic smile spreading across her sensual lips.”

The latter observation comes in the middle of the woman’s own confession: She is his former student Xuan, who pledged her life to the Communist Party after she was raped “right in my living room by two army officers, one American and one Vietnamese,” in 1964. She has been sent to infiltrate Minh’s group of defectors “and integrate myself into the Vietnamese community in the United States.” When Minh reluctantly gives Xuan up, the group leaders plan to murder her in the night.

Before they can do so, however, their boat is boarded by Thai pirates—one of whom takes Xuan “down into the cabin,” out of Minh’s sight, and kills her there. Whether or not the pirate successfully rapes Xuan is, to me, left ambiguous by Minh’s limited focalisation: He hears first their struggle, then “[a] deadly silence,” before the pirate returns “[l]aughing” to dispose of “Xuan’s broken body.”

(Exemplifying Nguyen’s theory about a tendency to read for resistance, I prefer to believe that Xuan was killed while fighting off the pirate, unlikely as that is.)

In the last pages of the novel, Blue Dragon, White Tiger suddenly tells a story that bears a heavy resemblance to the plot of The Sympathizer—with a striking difference.

Second spring

“Xuan,” I addressed her by the name I was convinced was really hers, “I knew from the first day on the boat that your real name wasn’t Lai. Perhaps in your too literary and sophisticated way of changing your name, you’ve betrayed your secret. I’m sure you know the saying, ‘Xuan Bat Tai Lai, spring never comes twice in the same year.’ I don’t understand why you denied knowing me.”

Where the narrator of The Sympathizer is a reluctant American, Minh is a U.S. green card holder who tells the Prime Minister of Thailand—his old classmate and friend—that “I plan to return to America as soon as possible,” to preserve—in the environs of New York City!—“the spirit of the historic Vietnam that he held in his heart… the mystic Vietnam,” now lost, “not the vulgar and brutal one.”

No: In Blue Dragon, White Tiger, the spy, sleeper, and spook is instead played by Xuan, a woman, “the communist agent,” no longer nameless.

I don’t have an HBO subscription, so I’m not sure when I’ll be able to watch The Sympathizer, but I want to. (It had better get renewed for a second season, if only because I’m masochistically curious as to how the producers will adapt The Committed, a chaotic text that emerges from Nguyen’s plan to write “dialectical novels grappling with the need for ideas to be constantly self-reflexive and changing.”)

What I’m also awaiting is the final chapter in the Sympathizer trilogy, in which, Nguyen has promised, the narrator “comes back to Southern California to make amends and seek revenge,” still “a man of two faces and two minds.”

I hope the communist agent comes back, too.